The Marriot Marquis Atlanta, GA Architect: John C. Portman Jr.

In light of the recent passing of John C, Portman Jr. I wanted to share a paper I wrote on my favorite building of his. Mr. Portman truly built Atlanta. The skyline you know and the city we love. I have always wanted to meet him but some things are not meant to be. Rest In Peace. Thankful his designs transcend time. Please note this paper was written in 2014.

John Portman at relighting ceremony for the blue dome of Polaris atop the Hyatt Regency Atlanta, 2014. Photo © BenRosePhotography.com

Known as one of the most influential and controversial architects of the twentieth century, John C. Portman Jr. not only created the modern Atlanta as it is today, but also built a design philosophy that breathes throughout his works, like the Atlanta Marriott Marquis. In his original architectural concept for the Atlanta Marriot Marquis, Portman expresses his principles and theories of design applied as the function, order and variety; nature and movement; and finally, human participation and spectating.

Instead of designing the Marriott Marquis as a stage for the new technologies, like other architects did, Portman instead states, “ Architects must redirect their energies toward an environmental architecture, born of human needs and responding to vital physical, social, educational, and economic circumstances”. The hotel was designed out of the need for additional hotel rooms and meeting spaces in the downtown area caused by the expansion of both the World Congress Center and Atlanta Market Center. The main concern was creating fully functional space based around the people who would use it rather than having function follow form, like so many other architects have and will do. Throughout his concept Portman alludes to an idea that has become one of the staples of his fame “Buildings should serve people, not the other way around”, the Marquis hotel’s function proves this point valid as eighty-five percent of the meeting or convention activities are all on one level for an ease of function to best serve people’s needs.

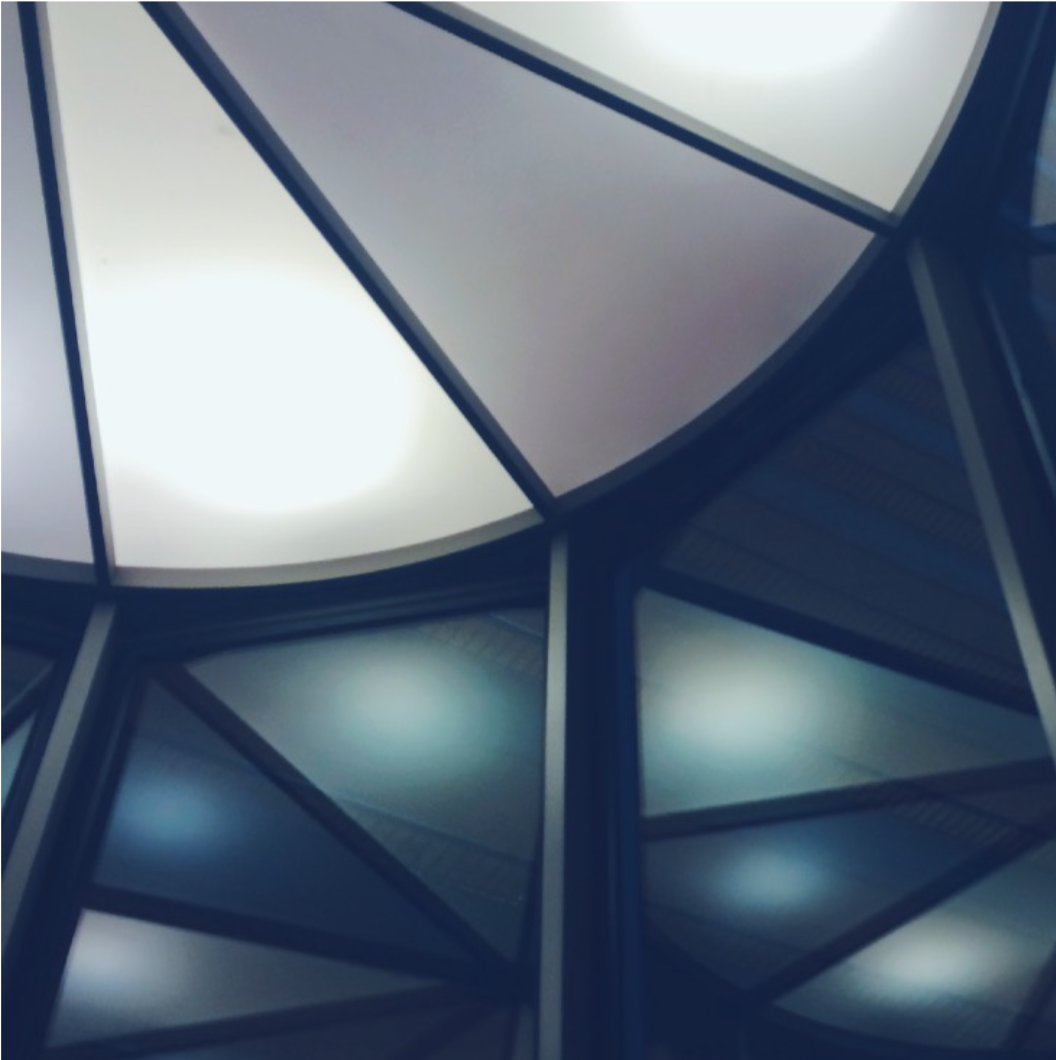

Harmony requires an agreement and combination of elements, thoughts, or ideas; in John Portman’s concepts, the combination of order and variety moving concurrently. In his architectural concept for the Marquis Portman shares “People require order in their lives, but they also crave variety”; the Marquis’ exterior and structure play as a prime example of this concept. The color and texture of the exterior, though some call it bland, was an intentional choice for the hotel to blend with the rest of the Peachtree Center, giving in to the order, but the structure itself, a low-rise podium, gives the variety among the Center. An argument could be made on the color choice used on the exterior that people could get the hotel confused with the surrounding buildings on street level due to the monochromatic tones used on the exteriors. The structure also has a play on harmony, which Portman articulated well from his original concept. The east and west ends of the structure provide order with their verticality and thinner width, while the north and south, longer ends, curve, then taper in and end in a rectangular shape. The exterior shows thought and restraint, while viewing there is almost an imbalance in the harmony that the variety may outweigh the order, but just as the feeling almost surfaces the structure tapers and the harmony resolves. The juxtaposition of the exterior is mimicked in the interior. While Portman mentions the harmony among the scale and intimacy in the atrium, the scale pulls ahead by the shear verticality of the forty-eight stories once the viewer breaks through to the space, it has a sense of grandeur and almost overcoming feeling. The order and verticality is only represented by the straight lines of the elevator side and the opposite side, those are then overwhelmed by the curves by not only of the exterior structure, but the curved wrapping balconies, that when viewed all in context give a resemblance to a large ribcage. Though in his concept he argues “It is not intended to be overwhelming, but instead to serve as an indoor experience of space as an element of nature”, the atrium walks a very fine line of the order between closeness and familiar with variety of grandeur and scale. Once above the lobby, looking down there is more of an understanding of the order and variety of the structure as well as easier access to more familiar and not as grand spaces; the two large stair cases attempt to weigh down the height of the atrium giving some tension but the height still outweighs it. On the forty-seventh floor viewing down it gives the viewer an almost daunting and uneasy feeling, a tension given by the repeating forms of the wrap around balconies on each level that seem as though it will never end. Viewing the atrium from the lower floors the spectators see an almost hollowness and caverness space but at the top the skylight opens it giving it a breath that the space so desperately calls for without the suspended sculpture. Portman’s approach to design comes from a different direction of the time, and with that comes a learned understanding of prioritizing the problems to solve and converging principles into a harmonious design.

Among Portman’s understanding of people needing order and variety, he also includes “People are also innately responsive to nature”, so he includes nature and movement to fulfill a need for an “environment oriented to people rather than to the creation of monuments.”. Elements of nature act as movement within the hotel by the light coming from the narrow east and west sides as well as the skylight over the atrium. Portman notes that light is least understood by architects and developers because both natural and artificial light can change the entire personality of the environment. The interior gets an almost ethereal feeling from the natural light during the day, and at night the artificial light was thoughtfully done to not take away from the space. Movement is shown on the exterior not only buy the curved structure, also an expression of nature, but buy the light moving along the shape of the building throughout the day giving a different play on light than most other building. More movement is shown in the Marquis by the glass elevator, giving the prompt for guests to move around the space. Portman views his elevators as kinetic sculptures feeling as though “Riding an elevator is another important transitional experience, and there is no reason why you must ride in a closed-in box”; instead of hiding an elevator like most do, he instead opens the walls replacing them with glass and jutting the shafts out to view the environment around. The concept of pulling the elevator out and using it as an important element was ingenious; it gives the large atrium space the natural movement it needs so it is not seen as still and silent, also it gives a divide to the massive atrium space. Besides the structural elements of the hotel, Portman also gives the obvious representation of nature through placing plants, fountains, and greenery throughout the space; adding to the organic movement of the space. Another element of both movement and nature is the large fabric sculpture suspended in the atrium. The sculpture moves freely giving a sense of airiness to the space as well as loftiness with the height; it also lends itself to almost an aquatic plant moving with the tides, which could go along with the whale rib comparison of the lobby. The red chosen for the fabric also gives the space a warmer feel, and shows better the interplay of light and shadow, along with matching the hues used in the carpeting around the hotel. Recently, the sculpture has been removed, and without it the atrium space lacks the balance of movement, but viewers are able to have a better view of the grandeur, mass, and verticality of the atrium. Light shows the material, structure and space as well as highlighting the natural elements within the environment created in the Marquis.

People are the center of John Portman’s philosophy on design; not only does he want to encapsulate them in an environment he wants to “Involve people in my architecture, both as spectators and as participants.” People are the reason and the intended users for the space so it only makes sense that the environment suits them, but what other architects and developers miss out on is allowing people to be an active part of the elements in the design. Portman executes his concept of participation in the Marquis in multiple aspects like the walkways linking the elevators to the balconies, adding a needed motion to an otherwise static and opposition to natural elements in the environment. The coming and going of guests throughout the lobby is a needed element to the ground level which balanced by the movement of the elevators which act as both an opportunity for participation and spectating. Guests interact with the elevator but they also can view the atrium being fully submersed in it. The open balconies allow for participation from guests as they wrap around the different floors to their rooms they add movement but can also use the space as a place to observe the surrounding environment like Portman’s concept of shared space “If more than one thing is happening in a space, if you can look out from one area and be conscious of other activities going on, it gives you a sense of spiritual freedom.” The openness in the atrium allows for people to not feel constrained in space and also to near other activities occurring.

The Marriot Marquis is truly a feat of modern architecture. Though the monumentality and verticality of the atrium can be overwhelming, compared to his original concept, Portman’s execution of the hotel reflects his theories of deign. For every element and environment created in the hotel, Portman gives a well-articulated reason in his original concept, even confronting the possible arguments or questions received about the space. John C. Portman works in a form follows function manner like in the case of the Atlanta Marriot Marquis, creating environments based on his understanding of human needs, their desire for harmony of order and variety, inclusion of nature, and the life that giving people participation in a space brings.

The following photos were taken by me in 2014.

Sources Cited

Portman Jr., John C. Architectural Concept for the Atlanta Marriot Marquis. 1985

Portman Jr., John C. John Portman & Associates: Design Philosophy.

Barnett, Johnathan, and John C. Portman. The Architect as Developer. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1976.

High Museum of Art. John Portman: Art and Architecture. Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 2009.

Leviton, Joyce Architect. John Portman: ‘I Violate Sacred Rules’ to Create ‘People Places.’ People Magazine Archive, August 11, 1975, 3pp.

Shoulberg, Warren. “John Portman: The Chairman.” Gifts & Decorative Accessories, January 01, 2011.

HTT. “John Portman Honored in Atlanta.” Home Textiles Today, October 21, 2011. p18

Home Accents. "AmericasMart: Looking Forward." Home Accents, November 01, 2009, pp 28-29.

Portman, John. Form. Victoria, Australia: The Images Publishing Group Pty Ltd, 2010.